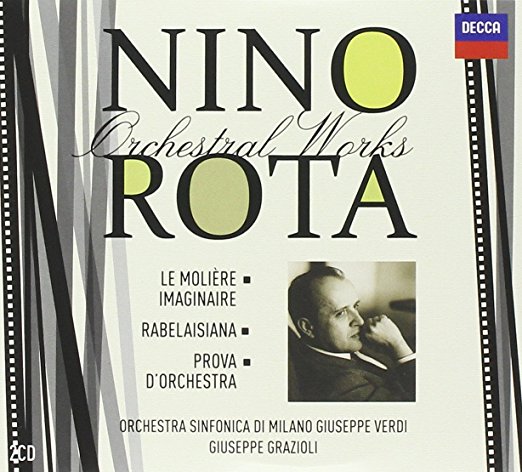

| Title | Nino Rota Orchestral Works Vol 3 |

|---|---|

| Category | Discography |

| Description |

Ensemble / Ensemble: Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi Direttore d’orchestra / Conductor: Giussepe Grazioli Disc 1: Le Moliere imaginaire (1976)*

Atto II / Act II

Disc 2: Prova d’orchestra Suite (1978)

Rabelaisiana for Soprano and Orchestra (1977)*

Concerto for Piano in E minor “Piccolo mondo antico” (1978)

PRIMA ESECUZIONE MONDIALE / WORLD PREMIERE* Casa Dicografica / Record Label: Decca Editore / Publisher: Recensioni / Reviews: Note alla discografia / Liner Notes: n 1976, Maurice Béjart, probably the most important choreographer of the second half of the 20th century, a great admirer of Fellini’s films and of the music Rota wrote for them, asked the composer to take part in his project to celebrate the tercentenary of the death of Moliére. A deep friendship and fruitful collaboration evolved between Rota and Béjart, which reflected the cultural background they shared. On December 3rd, 1976, the ballet-comedy Le Moliére imaginaire had it first performance simultaneously at the Comédie Française in Paris and the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. This was the greatest of Béjart’s many triumphs and the production enjoyed an equally successful European tour the following year before being eclipsed by newer projects. Shortly before his death, Rota prepared a suite from the ballet music, and this was first performed under his own direction in Naples on December 15, 1979. After his death, however, the suite was never played again in its entirety until recorded on BIS–CD–1070: Rota: Symphony No. 3/Concerto festivo/Le Moliére imaginaire-Ballet Suite (2001). The ballet music was once described as ‘a celebration with tragic pauses’ and the subsequent selections and elaboration of items for the suite might be regarded as a ‘celebration veiled by a gentle and irreverent melody.’ The suite from Le Moliére imaginaire omits the moments of sadness and more intense melancholy that, in the ballet, accompanied the many fluctuations in Moliére’s own life. Instead, it lays greater emphasis upon the theatrical synthesis which originally inspired Béjart and Rota; in Béjart’s own words: ‘For him [Moliére] a grimace, a burst of laughter, a song is as important as a beautiful line. Nature is life. Moliére is alive.’ The suite from Le Moliére imaginaire is one of the late Rota’s happiest scores, where the composer demonstrates his ability to mix different styles quite naturally, while maintaining a poetic and expressive idiom uniquely his own – even when he is recreating 17–century France in music. Prova d’orchestra/Orchestra rehearsal was the last collaboration between Fellini and Nino Rota. The film follows the travails of an orchestra rehearsal session that degenerates into a revolt and someone almost ends up being killed. Things are only cleared up when there is outside intrusion into the hall where the rehearsal is taking place, showing the awful fragility of the ferocious and quarrelsome species of animal that we are. To continue this sort of anthropological reading, while the killing might suggest a community under threat (the orchestra) making a human sacrifice in an attempt to find a cathartic salvation, the huge demolition ball that crashes into the building and opens up a whole new narrative dimension, is one of those Fellinian gimmicks: one that sends a powerful signal but is open to a host of different interpretations. Fellini made a point of saying that he took his inspiration from what he had observed at the recording sessions for the soundtracks to his films: the broad range of humanity represented by the musicians engaged for the sessions, and an often apathetic strain of humanity too, indifferent both to the work they are asked to do and the possibility of building relationships with their colleagues; a group of conscripts, a quarrelsome and potentially mutinous crew that, as if by magic, as soon as its members start to make music, becomes something harmonious, entirely at odds with the hitherto prevailing mood. As is always the case with Fellini, this is one part of the whole, the one that probably helped him to control his crew of actors and collaborators. But looking only at Rota’s score, prepared long in advance for its use on set, since it was essential to the filming, we find a cyclical suite in 5 sections [the final piece being a mirror of the first] which is a kind of summing up of the two artists’ lives. Together, Fellini and Rota had established an utterly distinctive musical language that was able to deal again and again – with an infinite number of variations – with the dramatic situations that repeatedly arise in Fellini’s cinematic language. Here the music conjures up a cheerful collective light-heartedness in the opening of Risatine maliziosie, embittered melancholy in I gemelli all specchio, a waltz Valzerino no. 72 that trips lightly between Laurel and Hardy (are these our two artists?) and then suddenly swells into the utmost sadness, only to fade away into an interlude, Attesa, where the listener is transfixed by a languid string melody that disappears into nothing. The sounds of a celesta opens the piece that is the heart of the work (and also the film): a Galop that takes on board a good deal of music from the first half of the twentieth century as it races along. As the accumulated material becomes more and more contrasting and explosive there comes an enormous crash, similar to the one in Passerella di addio that Rota composed for the soundtrack for 8 1/2. But where in the Passerella the screen imagery is matched by the sound of a solitary flute vanishing in the distance, here the loud, abrupt crash generates only an echo, out of which emerges a repeat of the skipping Risatine maliziosie tune. This time it develops into a trumpet theme (the trumpet being, together with the violin, the principal instrument of Fellini’s films) which is then taken up by the strings. The three orchestral songs Rabelaisiana also date from Rota’s final creative period: they were composed in 1977 at the request of the singer Lella Cuberli who at that time had won acclaim for her performances in Il cappello di paglia di Firenze, Rota’s most famous stage work. The composer was working with the limitations of a very short deadline for the commission, and he wrote some challenging music, possibly not best suited to Cuberli’s voice, but highly inspired in keeping with the texts he chose: three poems from Gargantua by Francois Rabelais (1494?-1553), a writer whose work Rota loved and responded to. In my opinion this is one of his most interesting concert works, but one which, possibly because of the demanding tessitura and the difficulties of pronouncing the text, has not yet found its proper place in the repertoire. Inscription takes us over the threshold and into the poetic world of Rabelais by way of inscription on the gate of the fantastic city of Thélème – a piece of invective in which the poet gives a fanciful list of the people who may not enter the city, the home of his art. Rota responds to the verbal inventiveness of the poem with a hobbling rhythm that is repeated throughout the whole piece in a series of variations that go from a grotesque march to a ‘quasi-waltz.’ The second song, L’oracle de la bouteille, follows on from the ‘separation’ of all those who have managed to break into that abode truth. Here it is necessary to enter into the mysteries hidden in the bottle, whose liquid makes it possible to reach a state of higher awareness and truth. The music makes use of a small melodic cell repeated throughout the whole piece, but without ever leading to a harmonic, resolution. The mood of uncertainty gives the impression of entering unfamiliar territory, a feeling that is emphasized by the aliening entry of the trumpet which, in the finale, seems to vanish into some unknowable music universe. The third song, Io Pean, is a Bacchic hym, an exhortation to lose one’s senses in order to discover that state of pure consciousness that is the only path to enlightenment. The achingly sad opening melody draws us into this escape route, accompanied by words that praise Bacchus and the magic bottle. The subsequent musical crescendo serves as a warning to all those who think that this is an easy road to miracles, or a shortcut on the uneven path of life on earth. In 1974 Rota wrote the soundtrack for the film Daniele Cortis directed by Marion Soldati, based on a novel by Antonio Fogazzaro (1842-1911). Fogazzaro was a leading figure in the Italian Romantic movement, and the film is an attempt to create a cinematic opera, giving the music the role of introducing and evoking the mood of Romanticism. The very opening of the film provides the music material for what would become the framework of the Concerto in Mi minore per Pianoforte e Orchestra (Piccolo mondo antico) (1971), which bears the subtitle Piccolo mondo antico, a reference to Fogazzaro’s most famous novel. Right from the concerto’s introduction, for piano solo, the theme of a farewell to a memory, to one of the most tainted and hazardous types of music, that of late Romanticism, seems to come strongly to the fore. And yet we are immediately aware that, as is always the case with Rota, the intention is never didactic or explanatory but simply functional: the composer is pressing into service elements that few composers would have had the courage (or recklessness) to use in the 1970s in order to construct a large-scale piece that sounds so old as to seem completely divorced from the date when it was written. The first movement which constitutes almost half the concerto, is constructed in sections from collections of musical material. After the opening, for the soloist, the orchestra vigorously takes a centre stage in a series of chordal blocks before the piano re-enters with a sequence of rapid arpeggios and staccato figures; only then does a dialogue, at first restricted to woodwind and soloist, get under way. The following concertato section gradually brings in all the orchestral instruments and leads to an increasingly close-knit dialogue that calls for great virtuosity from the soloist. An exposition of the theme first by the oboe and then the piano, with a subsequent fugato development and a series of variations leads to the particularly long and challenging cadenza. The movement closes with a reprise of the principal theme by all, a staccato piano figure and a final brusque chord for the strings. The second movement, the central part of the concerto, is both dramatic and elegiac in tone The string opening is immediately repeated by the soloist in a more meditative form, before a dialogue gets under way, in which the orchestral mood turns increasingly sombre. After this, almost like the clouds clearing after a storm, the music becomes more elegiac, but there is still an underlying tension, as if there were something happening within us that is beyond our rational control. This is music that invites us to relax and at the same time reflect. A subtle, flickering ray of hope seems to appear at the end of the movement, although the strings have deep, dark sounds. The third movement moves at a moderately fast pace, and, to stay with meteorological metaphors, seems to establish clear skies after the previous dark mood. The dialogue between soloist and orchestra also seems to broaden out, and although there is no lack of pathos, it seems to become increasingly playful, virtuosic and decidedly more sunny, as the piano is called on to use all its strength to stand up to the orchestra playing at full force. As the orchestra and piano whirl away, tossing ideas back and forth, the music sounds like a kaleidoscope of all the elements used in the construction of the concerto. Typically for Rota, it all comes to an abrupt close. The composer’s mother, the pianist Ernesta Rinaldi who had inspired her son in his creative work, notes in her diary in connection with his work for Soldati’s film: ‘I have finally seen Daniele Cortis in Bari: heavy, dull and monotonous. Soldati hasn’t been able to make the most of the plot; The music is almost inaudible, except for the title sequence and the end; A shame, because the theme is lovely, and one of Nino’s best.’ It might just be that in this last piece for the concert hall Rota was paying homage to his mother, who had derived such enjoyment from the music. Francesco Lombardi |

| Date | 2013-Nov-9 |

| Publisher | |