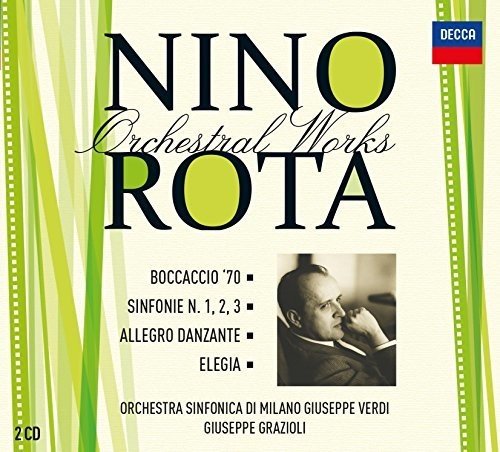

| Title | Nino Rota Orchestral Works vol 6 |

|---|---|

| Category | Discography |

| Description |

Disc 1 BOCCACCIO ’70

CORO DI VOCI BIANCHE DE LaVERDI

SILVIO ROSSOMANDO-Sassofono contralto SINFONIA N.2 IN FA “LA TARANTINA-ANNI DI PELLEGRINAGGIO”

Disc 2 SINFONIA N.3

ELEGIA per oboe e pianoforte

Luca Stocco-Oboe SINFONIA N.1

BOCCACCIO ’70

*World Premiere Recording ORCHESTRA SINFONICA DI MILANO DI GIUSEPPE VERDI Editore/Publisher: CD 2: 1-4 Schott Music Note alla discografia/Liner Notes NINO ROTA A tiny man, elusive, apparently shy and delicate, and, for all his fame, a man who guarded his privacy, but a man with two penetrating eyes. That was how Nino Rota often appeared to people. “Whatever the setting, whatever the occasion you met him in, whatever the initial or potential reasons for your meeting,” Federico Fellini once said, “he always gave the impression he just happened to have turned up, while at the same time giving you the confidence that he could be relied on, that he had time to spend with you.” Those restless eyes were, in fact, one of the many indications of his complete imperviousness. “The frictions between his interior life and the ‘world'”, wrote musicologist Fedele D’Amico, “miraculously managed to generate energy, orderly precision and masterly scores, and gifts that were gossamer light and perfect for their context. So, while no one ever found themselves surprising him in the tiniest flash of anger, it was not because his reactions were half-hearted, but rather that they were to the point. His reply to an authoritative scholar who made the pronouncement, ‘Busoni’s Doktor Faust is the finest opera of the century’ was ‘You have no manners’.” Brilliant. A surreal riposte worthy of the great Italian writer and humorist Achille Campanile. Rota’s personality was seemingly simple and impenetrable, just as his music continues to seem today, and mysterious for a number of reasons. But nevertheless, those who got to know him well had no difficulty identifying the mechanism that regulated his existence: a total bond between music and life. A complete musician is how Fellini once described him, on another occasion. “He lived in music with the freedom and contentment of a creature that lives in a dimension they find naturally congenial.” And to quote Alberto Savinio, younger brother of De Chirico, “He is the most ‘musical’ musician I know. I mean that he lives ‘only’ in music, and only there is he happy. […]There, every effort in life, every material effort disappears; and since even playing is a mechanical action and therefore an effort, Nino Rota plays as if on behalf of someone else. Who? Music.” Rota used to say that for him music was not a passion but rather a vice. In fact, he practised music as if it were a natural language, like the spoken word. His art and his very conception of it stood for a kind of voracious but gentle compositional fury. From an early age he simply enjoyed music, and he fulfilled his need to switch between registers with complete freedom and the utmost flexibility. “I learned everything I needed from a sol-fa school that I used to go to when I was seven… after a year of lessons I knew how to write everything I wanted to, despite being nothing like an exemplary student, indeed, the exact opposite. Then I wrote symphonies, oratorios, I filled acres of manuscript paper because fun for me was making music.” And so it would be until the very end. Alongside the fury, however, there was the industrious forge of the musical “alchemist” who, living in an idealised zone between the past and the present, between reminiscences and the modern day, triggered a flurry of allusions, borrowings, elaborations, transfusions, self-quotations and parodies. An artistic process adopted into a modern sensibility that led to an unstoppable, original and uninterrupted profusion of music. This never-ending flow that lasted a lifetime, and was expressed with a multifarious, eclectic and chameleon-like spirit (there are stories of Rota’s ability to perform a famous piece as if written by the most varied composers), which had the capacity to reach the listener directly: “This immediacy, this spontaneity,” to quote D’Amico again, “is perhaps the feature that most distinguishes his music from that of his contemporaries […] to the extent that it can convey small or large-scale emotions in their immediacy, their spontaneity. This is his specific virtue, his message.” As mentioned, the “vice of music” quickly entered the life of the young Rota, born in Milan in 1911, and it made a grand entrance, by way of a family that predestined the young boy for music. His grandfather Giovanni Rinaldi was a composer and pianist; his grandmother Giovanna Anfossi, was a pianist. Two cousins, both girls, were a singer and violinist respectively, while his mother Ernesta was also a pianist. The boy was bursting with artistic talent (at the age of eleven, after the death of his father Ercole, he had even composed an oratorio, The Childhood of St John the Baptist), and his mother made sure he took a regular course of study, first with Ildebrando Pizzetti, and then in Rome with Alfredo Casella. In 1929 Nino took his diploma at the Conservatory of Santa Cecilia. Then, thanks to the support of Toscanini, he obtained a grant that allowed him to enter the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. This American experience had significant consequences for Rota on both a personal and musical level: it marked the end of the child prodigy, and the beginning of the mature artist. After returning to Italy he had a period of reflection, with little work, and then, around the mid-1930s, his first compositions of indisputable interest started to appear. This is the period that saw the creation of his first two symphonies: perfect examples of the sophisticated, approachable music of those years, in a style that was already happy to absorb popular music and irony, and allow the influence of Stravinsky, Ravel, Sibelius, Shostakovich, Dvofak, Vaughan Williams and Mahler to come to the fore, but all blended together to create his own distinctive voice. Both symphonies are in the time-honoured four movements, and, with an original, linear expressivity and pronounced taste for melody, they reflect the French neo-classical tendency that had taken hold in the USA in the years between the wars. At several points, however, the music turns the style’s natural “soundscape” towards an idealised and affectionate evocation — not mere description — of the sunny, optimistic spirit of the southern Italian land of Puglia. Rota had moved there in 1937 to teach theory and sol-fa at the Liceo Musicale in Taranto, and subsequently, from 1939, in Bari. In 1950 he became Director of the Bari institution. These works have nothing especially complicated about them in terms of language, but there is no denying the high level of sophistication in the orchestral technique displayed. Take, for example, the almost “pastoral” nuances in the first movements of both, which seem truly to be taking place in the open air.

Rota worked on Symphony No.1 in G major between 1935 and 1939; on this disc we hear an alternative version the composer prepared, with the second (Andante) movement missing. No date is given on the manuscript, but from the type of paper used by the composer we can presume that it was made — for reasons we are not aware of — in the 1960s, and involved changes to the instrumentation and a number of cuts to make the musical discourse more fluid.

Symphony No.2 in F major, on the other hand, was composed between 1939 and 1945, and then revised in 1975 on the occasion of the first public performance, given on 14 April that year in the Teatro Petruzzelli in Bari. The partly Mediterranean, partly Lisztian subtitle, “La Tarantina — Anni di pellegrinaggio”, refers to the composer’s time in Puglia. The outer movements provide a perfect opportunity to flaunt an engaging lyrical, nostalgic note that passes between the solo players of each section, singing of a simple Italian rural life, while the more elaborate second movement makes room for a playful but strict use of counterpoint. During the war Rota managed to avoid being sent to the front, and his national service was cut short. As soon as he had carried out his military obligations he returned to Bari and his post at the Liceo musicale (which, in 1959, would be promoted to the level of Conservatory). In 1954 his mother died. She was a powerful character, an anti-conformist woman of great sensitivity, and had always been the composer’s rock.

The following year the composer produced an Elegy for oboe and piano (Un poco lento): one of those many chamber pieces intended to be played by friends, colleagues and pupils. Pieces in which it is possible today to find Rota at his most intimate and spontaneous, caught between elegance, subdued melancholy and smiling conviviality; at the same time they very often contain themes that re-appear later on in film scores. Here, an inspired, singing oboe melody emerges over an unchanging, repetitive piano backdrop. It is often the case in Rota’s scores that it is a woodwind instrument that gives out the melody, becoming the first engine of the musical action.

Between 1956 and 1957 Rota worked on his Symphony No.3 in C major, again in four compact movements. This is an anomalous work, to a certain extent, in that it is decidedly more mature, more sculpted, more solid, more organic and more attentive to the wider world of 20th-century music. The musical language is strikingly immediate, but personal too, in the final reckoning. Unsurprisingly, attention has been drawn to the many affinities with Prokofiev’s Symphony No.1 “Classical”, and other of the Russian composer’s works, with which the Rota’s Third shares the energy, biting string phrases, dissonant melodic lines, unexpected bold harmonic strokes, and dramatic, nocturnal dimension that we can feel in the second movement. Rota had made his debut as a film composer in 1933, when he worked on a film for regime called Treno popolare. After the war, his family’s critical financial situation had led him to accept other, similar offers. Between 1942 and 1950 he had provided soundtracks for 41 films, and the cinema world had become his principal client. In the 1950s he produced another 77 scores, launching important and crucial collaborations with Luchino Visconti, for instance, and most especially with Fellini, whom he started working with in 1952, on The White Sheik. The 1960s saw Rota’s definitive consecration as a film score composer; it is the area of his artistic output for which he is best known if not, in many cases, solely known. More than 150 titles exemplify the subtle work of music integrated with image, of musical support to action, and psychological definition of characters. In any case, reading the list of Italian and international directors Rota collaborated with is rather like going through the history of cinema over the last few decades. As well as those mentioned above, we also encounter such names as Comencini, Monicelli. Lattuada, Soldati, Tampa, Camerini, Castellani, Petri, Wertmuller, Ferreri, De Sica, Leffirelli, Eduardo De Filippo, Vidor, Vadim, Malle, Bondarchuk and Coppola. Rota said that the cinema had been for him a school of music and musical practice, and it was undoubtedly in the fevered world of cinema that he found the right terrain to for his talent, one that leant towards bringing down barriers and collapsing the hierarchy of genres. It allowed him to make best use of his great skill as a communicator, his ability to adapt quickly to ever new and changing situations, in a permanent state of coming into being. All these qualities made him incredibly valuable in the eyes of directors.

In 1962 he worked on Boccaccio ’70, a film in four episodes inspired by the Tuscan writer and poet’s Decameron, focused on the theme of sex in Italy in the 1960s, and entrusted to four important Italian directors of the day: Mario Monicelli (Renzo e Luciana), Federico Fellini (Le tentazioni del dottor Antonio), Luchino Visconti (Il lavoro) and Vittorio De Sica (La riffa). Rota wrote the music for the second and third episodes. In The Temptation of Dr Antonio, the unbending moralist Antonio Mazzuolo (Peppino De Filippo) ends up utterly seduced, to the point of obsession and completely losing his mind, by the image of Anita Ekberg on an advertisement inviting people to drink more milk, with all the associated erotic allusions, amusingly emphasised by Fellini. These include a jet of water from a garden hose that a workman is using to water the buxom Swedish actress’s bosom. Rota clothes the disparate, surreal humanity — boy scouts, prostitutes, black American musicians, priests, schoolboys and riflemen — that acts out the grotesque Roman story in characterful and imaginative musical dress. In Lavoro, on a screenplay by Suso Cecchi d’Amico and Visconti himself, taken from Maupassant’s short story Au bord du lit, we see a minimalist, introspective and wordy psychodrama, set — on the principle that opposites intensify each other — in the vast rooms of a luxurious, noble interior in an icy Milan. The arrogant Count Ottavio (Tomás Milian) is mixed up in a scandal surrounding a string of escorts. His wife Pupe (Romy Schneider), tearfully forces him to pay him for the sexual favours she will bestow. The Waltz that Rota gives her character takes on importance as the action develops. It is a gentle, lulling piece, with the most delicate, almost fairy-tale orchestration, that vanishes into nothing, offering a melancholy, sensual portrait of an outraged woman, alone and depressed, essentially resigned, despite the appearances of her new demands.

The Allegro Danzante in D minor for clarinet and piano dates from the last years of Rota’s life. He composed it in 1977, while spending the summer in the spa town of Fiuggi, and here we hear it in a version for piano and alto saxophone authorised by the composer himself. The piece is in three sections, and is a perfect illustration of Rota’s inventiveness, his infallible sense of how to use chromatics and harmony laden with atmosphere. While the keyboard plays a easy, gently percussive accompaniment, the saxophone floats a mysterious, dreamy melody. Rota died in Rome on 10 April 1979, while leaving the clinic where he had had to undergo tests. For some time, he had suffered from a cardiac complaint which he chose not to have treated surgically. One day he declared, “When they tell me that in my music I’m thinking only of bringing a little nostalgia and a lot of good humour and optimism, I think that that is exactly how I would like to be remembered, with a little nostalgia, and lots of optimism and good humour”. Massimo Rolando Zegna Testo/Text Boccaccio ’70 Bevete più latte, Bevete più latte, Bevete più latte, |

| Date | Dec-17 |

| Publisher | |